Collecting Aspidoscelis neomexicanus accross it's range

Vicente, Angie, Dallin, and Randy ("El Equipo Huico") spent two weeks in the field catching New Mexico whiptail lizards (Aspidoscelis neomexicanus). In 2023 Vicente and Randy found a population of New Mexico whiptail lizards in Saint George, Utah. This is the third known introduced population of New Mexico whiptails (the others being near Salt Lake [UT] and Holbrook [AZ]). Vicente asked whether the Saint George population was from the same source as the other introduced population, and so we decided to figure it out! (more text beneath the photos).

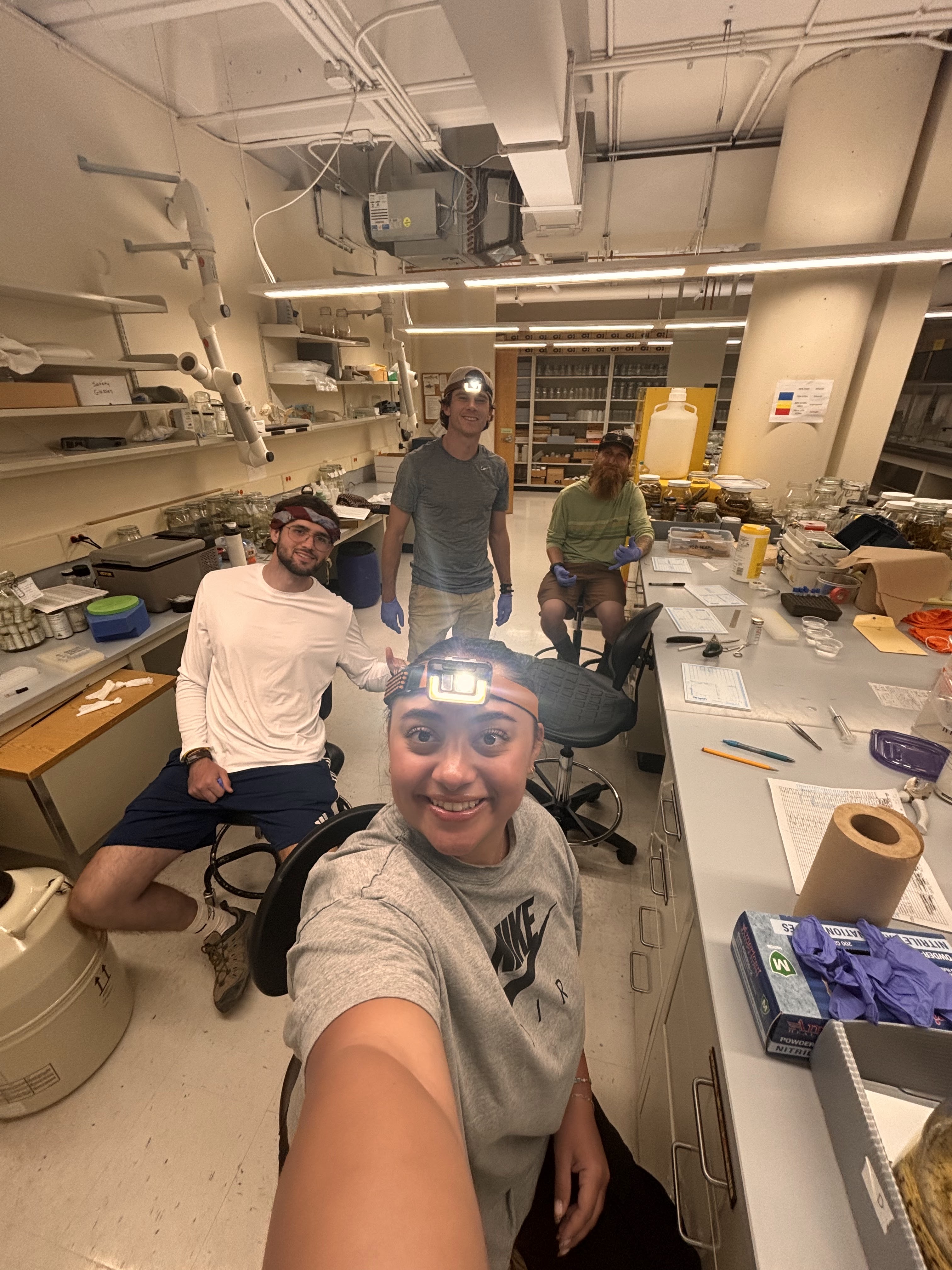

Randy, Vicente, Angelina, and Dallin camped at multiple sites in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas to collect A. neomexicanus from native and non-native populations. We will use these samples to figure out the source region for the non-native populations and also test some other questions about the biology of introduced species. During our adventure we worked at Petrified Forest National Park, the University of New Mexico Museum of Natural History (with the help of Tom Giermakowski), New Mexico Tech (with the help of Dr. Joel Sharbrough), New Mexico State University (with the help of Obed Hernández-Gómez), and the University of Texas at El Paso (with the help of Océane Da Cunha and Miles Horne). We found many other beautiful critters along the way and did our best to dodge the many monsoons that we came across!

Aspidoscelis neomexicanus is a great model for understanding the biology of introduced lizards because (i) it is a parthenogenetic species [i.e., only female species that reproduces through cloning] and (ii) it can be found in abundance where populations have established. Because this species is parthenogenetic, that means that all individuals in an area have the same genes (unless mutations have arisen). This allows researchers to more easily identify the dispersal patterns of the non-native populations.