This post is a copy from my (Randy) personal website, but I thought it would be helpful to copy it here

Understanding the evolution of organisms that reproduce asexually has been of interest to biologists for the past century. However, because of technological limitations we had little understanding of their genomic structure. With increased accessibility to high-throughput sequencing technologies, examining the genomic characteristics of model and non-model asexual lineages is now feasible. In this blog, I will review publications in the field of asexual genomics as of February 2022.

New species is "missing link" between diploid sexual and triploid asexual species

Barley, et al. (2021)

In vertebrates, there is some correlation between ploidy level and asexual reproduction (asexual organisms are more likely to be polyploid than sexual organisms). It has even been proposed that the increased genomic diversity that accompanies novel genome incorporation helps asexual lineages compensate for the detrimental effects of reduced genetic diversity. Whiptail lizards (genus Aspidoscelis) are a great model for understanding questions related to vertebrate asexual reproduction, given that roughly one-third of their genus is unisexual. Many of these unisexual species are polyploid, but whether these lineages evolved directly from diploid sexual species or if their evolutionary history included an intermediate asexual diploid step is not defined for each of the lineages.

Barley et al. set out to understand the mechanism leading to the triploid parthenogenetic lineages of A. opatae, A. sonorae, A. uniparens, and A. velox. Previous hypotheses by whiptail pioneers Charles J. ("Jay") Cole (American Museum of Natural History) and Herbert Dessauer (Louisiana State University) suggested that these lineages arose from hybridization events between species from the A. inornatus complex and the A. burti complex (shown in photo above).

Paternally-biased allele expression in Amazon Molly

Yuan Lu, et al. (2021)

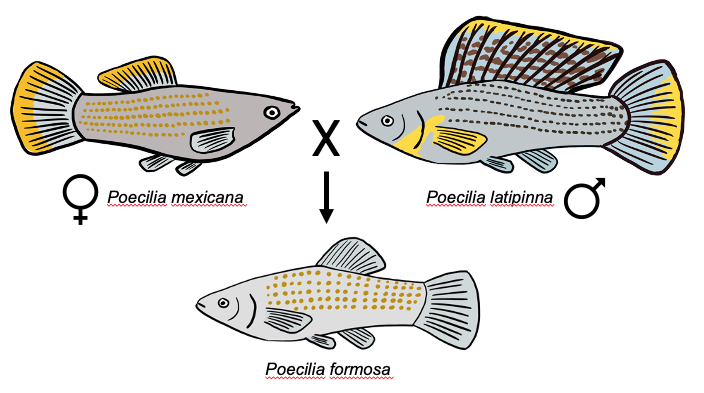

The Amazon Molly (Poecilia formosa) is an asexual fish (specifically gynogenetic) that is the result of a hybridization event between the Shortfin Molly (Poecilia mexicana and the Sailfin Molly (Poecilia latipinna).

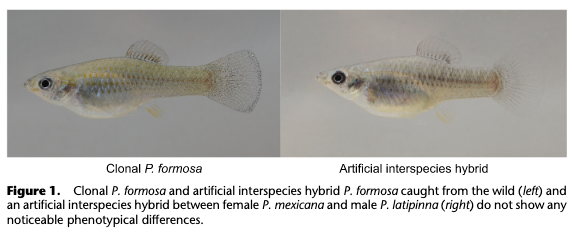

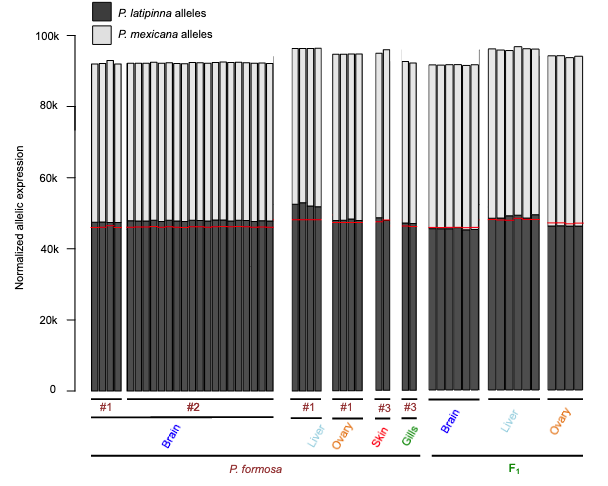

Lu et al. examined transcriptomes from lab-raised P. formosa and compaired them with F1 hybrids resulting from a cross between P. mexicana and P. latipinna. To do this, they collected P. formosa, P. mexicana, and P. latipinna from Mexico and brought them to research labs in Germany. They crossed P. mexicana and P. latipinna individuals to get an F1 similar to P. formosa (Although this was the nearly the same cross that resulted in the origin of the P. formosa lineage, it is important to keep in mind that multiple nuances [such as variation among the parental populations and the accumulation of mutations since the reticulation event] mean that these F1s are different from P. formosa).

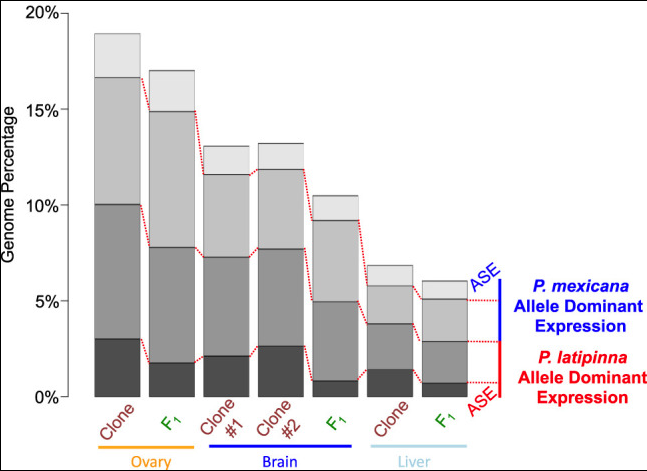

While the F1 offspring showed no overall pattern of parental bias in allele expression, P. formosus expression favored paternally inherited alleles (e.g., the P. latipinna alleles).

Most genes with allele-biased expression maintained low levels of the minor-expressed allele, however others silenced the alternate allele (allele-specific expression). This pattern was observed in ovarian, cerebral, and hepatic tissue.

Allele silencing at mitochondrial loci in asexual fish

Matos et al., 2019

Squalius alburnoides is a small, freshwater Cyprinid fish that reproduces asexually via gynogenesis. These fish contain hybrid genomes resulting from an ancient cross between Squalius alburnoides and Squalius hispanica. Matos et al. set out to understand how expression is regulated in these fish of hybrid ancestry.